In collaboration with Anti-Deception Coordination Centre (ADCC)

“I was between employers and saw this advert on Facebook from an online clothing store looking for salespeople,” shares Maria (not her real name), a migrant domestic worker (MDW) working in Hong Kong. “It said no experience was needed, training would be provided, and my time would be paid for. They were offering $300 per hour – I was so desperate, I decided to message them.”

What Maria didn’t know at the time was that she was entering into the first phase of an elaborate fraudulent scheme commonly known as a ‘brushing scam’. Perpetrators place job advertisements on social media, offering applicants online jobs such as working for an online store, click farming (clicking on links or buttons), or viewing videos in exchange for payment. Terms like ‘flexible working hours’ and ‘no experience or qualifications needed’ suggest a low bar of entry, enticing victims like Maria to apply.

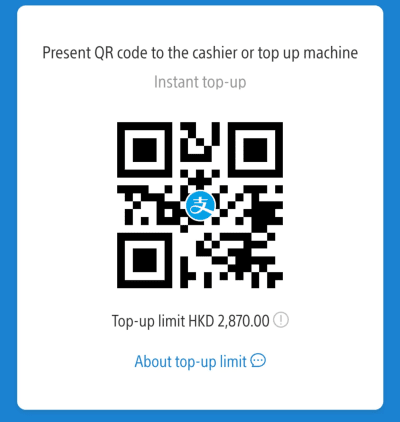

“I was paid $300 in advance to create this website login and begin my ‘training’, which was purchasing orders and sending them off for delivery,” Maria tells us. “I was asked to use money from my own bank account to place the order initially, but they told me that once I reached 35 orders in 3 days – an easy task, they said – I would be fully reimbursed for the payments and receive a big commission on top. After the first few sales, they did pay me back with commission as a ‘goodwill gesture’, which motivated me to try and reach my target.”

This is a huge part of the modus operandi of these brushing scams; giving a little amount back to the victim initially to hold their interest and build their trust, believing they will receive a big payout in the long run. Once the amount they have given the scammers becomes so big however, it is difficult to give it up, leading to victims paying out more and more money. This phenomenon is known as a sunk-cost fallacy, where someone is reluctant to give up on something they have heavily invested in, even when it is clear they are increasingly losing out.

“They constantly communicated with me through a messaging app, asking me to place as many orders as I could to reach 35 items. But by this point, I had already used $4,000 of my own money and I just wanted it back,” Maria recalls.

“After pleading with these people to give my money back, the woman told me to transfer any amount I had that day to pay for a few more transactions and then they would send me back all my money plus commission. So I borrowed more money and sent another $3,000 to them.

“As soon as I transferred the money, they immediately disconnected their mobile phone number. This is when I had the awful realisation that I had been scammed. It hurt so much as I don’t earn a lot, and I had borrowed money from a friend too. It has been a lesson learned the hard way: I am much more wary of offers on social media and messaging apps these days,” she shares tearfully.

Maria’s story is far from unique; in the first half of 2023 alone, Hong Kong police recorded a total of 2,139 cases of online employment fraud, involving financial losses of up to a staggering HKD $441m. Still, there are many cases that go unreported, especially in the MDW community, where a victim’s vulnerability and visa status can easily be exploited by scammers.

The minimum wage in Hong Kong for MDWs is HK$4,870; most of this is sent back to families in their home countries, with the rest saved or set aside for personal use. In Maria’s case, she still had to pay back her friend on top of losing her own money. That is another sad realisation in cases like this; recouping the money lost is almost impossible. Most of these criminal organisations have international money laundering networks which their illegally obtained funds are ‘washed’ through, to quickly disguise their true origins.

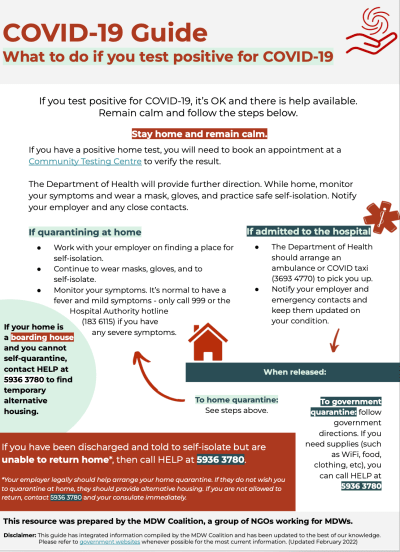

So, how do we avoid falling prey to these scammers? Firstly, as the old saying goes, if the offer seems too good to be true, it probably is. There may be times when we are struggling and such opportunities might look particularly appealing; however, these are also the times we can be at our most vulnerable, so taking a step back and checking the validity of the proposition is a good start. Watch out for terms like, ‘flexible work hours’, ‘we will pay as high as X amount for your free time’, and ‘no experience needed’ – this are common strategies used by scammers and potential red flags.

Always research any company or agency before using their services: make sure they are registered and licensed. Never provide personal or financial information to strangers, especially if they are asking for money.

To further protect yourself, stay informed about your rights and seek guidance from trustworthy sources. If you need police advice on scams, you may call their Anti-Deception Coordination Centre on 18222.

Employment fraud: “Click farm trilogy”

1. Recruiting click farmers

· Scammers place job ads on social media to recruit “click farmers” or “operators” whose duty is to shop via online shopping platforms to boost sales. Applicants are told they can earn commission based on their number of sales

· Phrases such as “work from home”, “flexible working hours”, and “no experience necessary” are used to lure applicants

· Scammers often just provide a social media contact to applicants

2. Requesting advance

· Scammers interview victims via social media. Once recruited, victims are asked to use online shopping platforms to put goods into shopping carts, then send screenshots of their orders to their recruiter

· Victims are then instructed to pay for the goods via a personal bank account (not a company account), but are assured they will be given a refund plus a commission upon completion of their work

3. Asking for further payment

· Scammers initially keep their promise; the shopping amount plus commission is paid back to the victim, thus tricking the victim into believing them

a7627e2f507e336b59c20ad92813c0f7)

9dde49c3be6bac6166d59fb7abf39532)

(1)4b7355993ca6165c683913d00254e725)

6c2435b2dd0927f22b3222b88d21fb70)