HONG KONG IN THE LATE 1970s: Governor Murray MacLehose is at the helm; the newly formed ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption) is in full clean up mode; the metric system has been recently introduced; and the Cantopop genre is gaining momentum.

Across the South China Sea in the Philippines, President Ferdinand Marcos’ recently implemented labour code sees the country opening its doors to reforms, including the overseas export of labour in the form of migrant domestic workers (MDWs).

With Hong Kong’s economy prospering and two-income households becoming increasingly common, the demand for migrant labour steadily grew. By 1976, there were approximately 2,000 MDWs employed in the city. One of those workers was Qualee Labrague Alonzo.

Qualee was born into poverty in 1948, in the remote fishing village of Jiabong, Samar. The eldest of 9 children, she bore a heavy burden of responsibility in the family. While her Tatay (father) spent his days fishing, her Nanay (mother) enjoyed her drink a little too much, leaving the kids to largely fend for themselves. Inevitably, when the younger ones got into trouble, it was Qualee and the older siblings who incurred the wrath of their parents.

Knowing in her heart that there was no future for her in Samar, Qualee made the decision to leave as soon as she turned 16. With no money, no education, and nothing but her wits and street smarts about her, she braved her way into living with an aunt in Manila. Finding work as a housemaid during the day, her evenings were spent busily upskilling, attending stenography and dressmaking classes as she planned her next move.

Following a lead from a friend about work opportunities, new certificates in hand, Qualee packed her bags and headed for Angeles City, Pampanga, to the US-run Clark Air Base. She was immediately offered a job as a caretaker, working for an American Air Force Officer named Captain Emerson. And it wasn’t long into her employment before Qualee met her Romeo.

Romeo, or Romy to his friends, was a jeepney driver. He drove every day from 6am to 8pm, earning just enough to survive. But Romy had bigger dreams, and after crossing paths with Qualee, he knew he’d found his someone to share them with.

After a year of dating, Qualee and Romy moved in together. They both had hopes for a better life, nothing grand or too ambitious: a house, food on the table, a good education for their children, and escaping the poverty they’d both lived through growing up.

But the road ahead was rocky. In 1974, Captain Emerson returned to the US, leaving Qualee without a job. One stormy day, struggling to make ends meet, Romy passed by his grandmother’s house and picked a papaya from one of her trees. That day, he hadn’t earned enough from the jeepney to allow him to buy food, so he brought that single papaya home to Qualee for dinner.

As they both sat around the table, Romy slicing the papaya, he made Qualee a promise: “Pangako ko sa’yo, simula bukas, hinding hindi tayo kakain ng papaya para sa hapunan,” (I promise you, starting tomorrow, we will never have papaya for dinner). They ate the papaya in silence, Qualee’s tears quietly streaming down her face.

Despite the challenges and setbacks, Romy and Qualee remained determined. They started to explore overseas opportunities, and with the growing demand at the time for female migrant workers, it was Qualee who first secured a job in 1976, as a domestic worker in Hong Kong.

It was a big step, not least because Qualee had given birth to their eldest daughter, Darlene, only a year earlier. Leaving her young family behind was tough, but the thought of securing a better future for them provided plenty of motivation. Whenever she suffered feelings of homesickness or longing for her family, sacrifice and resilience remained her mantra.

One stormy day, struggling to make ends meet, Romy passed by his grandmother’s house and picked a papaya from one of her trees. That day, he hadn’t earned enough from the jeepney to allow him to buy food, so he brought that single papaya home to Qualee for dinner

Qualee’s first employer in Hong Kong was a lovely Indian family with two young children. They were very kind to her, and even kept in touch decades after the end of her contract. When they subsequently immigrated to the UK, Qualee returned home to the Philippines while she waited for a new employer.

As she stepped off the plane in Manila, she navigated the crowds in Arrivals, searching for Romy and Darlene. When she set eyes on them, it felt like her heart stopped beating; she held her breath until she had them in her arms. Both Romy and Qualee were crying tears of joy.

A month later, Qualee was Hong Kong-bound again. At Qualee’s request, her new employer, a Portuguese businessman named Rey DaSilva, also agreed to sign Romy as his driver and personal assistant. Darlene was left in the care of Qualee’s sister, Terry, in Angeles City.

Romy and Qualee were happy: they had friends, their own living space in Ray’s sizeable flat in Happy Valley, and they always had food. They sent money back to Terry for Darlene’s school, food, clothing, and other needs, and made sure she was always well taken care of.

In November 1981, Qualee and Romy welcomed their second-born, Aileen, named after Qualee’s favourite RTHK Radio 3 presenter, Aileen Bridgewater. Rey became Aileen’s godfather.

Following Aileen’s arrival, Qualee decided to go back to the Philippines for good, to look after 7-year-old Darlene and her new baby. She opened a fashion boutique in Angeles City making tailored dresses, uniforms, and curtains; it quickly became a success, and things really seemed to be going well for her family.

Over in Hong Kong, Romy would send money back to the family each month. Despite the distance, Qualee and Romy remained close, exchanging letters every week with updates about their lives and children. Qualee would share how much Darlene loved her baby sister, bringing her candy or little toys after school, “Hindi pa pwedeng magkendi si Aileen, anak. Baby pa kasi sya,” (You can’t give Aileen any candy, dear. She’s still a baby). She said she knew they would be best friends when they grew up, and Darlene would always be there for her little sister.

One warm October afternoon in 1982, Qualee was busy in the shop sewing clothes, while Darlene was out playing in front of the store with her cousin. Suddenly, her sister Terry came running in screaming, “Ate! Ate! Si Darlene, nasagasaan ng jeepney! Ateeee!” (Elder sister! Darlene was run over by a jeepney!). On the way to the hospital, Darlene took her last breath in Qualee’s arms.

Romy arrived at Manila airport, not knowing any details about why he was asked by Qualee to urgently fly back from Hong Kong. But not seeing Darlene at Arrivals to greet him – he immediately knew. Romy’s legs gave out from the weight of the agony in his heart.

Nothing can compare to the intense sorrow of losing your child. In the beginning, the grief manifested itself as anger for Qualee. Anger at herself, anger at how unfair it was, anger at the jeepney driver who ran Darlene over. But the cloud of anger lifted, and gave way to understanding, and a spectacular moment of virtue: Qualee ultimately forgave the man who accidentally killed her daughter.

While he was behind bars, Qualee listened to his story. From a very poor family, he drove a jeepney purely as a means to survive and provide for his children. He hadn’t seen Darlene run into the road, but as a father himself, he acknowledged his guilt and the pain he had caused. He was ready to do time for what he had done.

Qualee thought back to when she and Romy were living off his jeepney driver earnings, the crushing poverty, the papaya dinner, and how their life since had been a blessing. Sharing the story with Aileen many years later, Qualee recollected: “Pinatawad ko sya, kawawa naman kasi siya, anak. May pamilya din siya, at aksidente naman ang nangyari,” (I forgave him, I felt sorry for him. He has a family too and it was an accident).

“Pinatawad ko sya, kawawa naman kasi siya, anak. May pamilya din siya, at aksidente naman ang nangyari” (I forgave him, I felt sorry for him. He has a family too and it was an accident)

– Qualee Labrague Alonzo, on her decision to forgive the jeepney driver who ran over and killed her 7-year-old daughter Darlene in 1982

A few months after Darlene’s passing, Qualee, Romy, and Aileen returned to Hong Kong together. Having been born in Hong Kong, Aileen held a British National Overseas (BNO) passport, giving her Right of Abode. By 1983, Qualee and Romy were also granted unconditional stay.

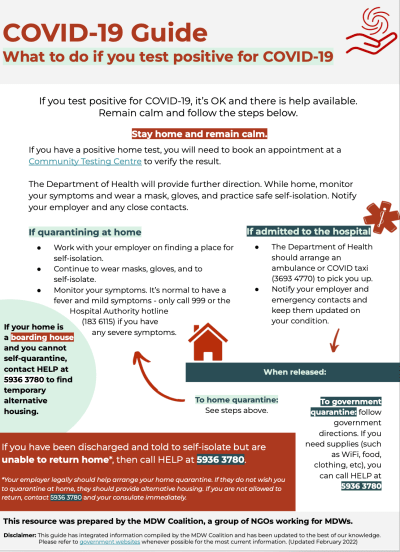

There have been several amendments to the law since then, including the broadening of the definition of ‘ordinarily resident’ to exclude MDWs, thus making any application for Hong Kong residency almost impossible for domestic workers.

This is evidenced in the case involving Evangeline Vallejos and Daniel Domingo; both worked as MDWs in Hong Kong for decades. Despite the Court of First Instance ruling that both applicants had fulfilled the conditions of residency – taking Hong Kong as their only permanent home and being ordinarily resident here for seven years – The Court of Appeal of the High Court subsequently overturned the decision on Vallejos’ case in 2012. Vallejos and Domingo then jointly appealed to the Court of Final Appeal, who rejected their appeal on 25th March 2013.

This closely watched case divided opinions. Eman Villanueva, spokesman for the Co-ordination Body for Asian migrants, stated in an asianews.it article, “The ruling actually gave its judicial seal to unfair treatment and the social exclusion of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong.”

According to the BBC, however: “Both the government and a pro-Beijing political party have said that allowing foreign domestic helpers to have permanent residency in Hong Kong would open the floodgates to their relatives, including children, who would require housing and education which would create a social welfare burden.”

Although Qualee didn’t have a taste for politics, she did what she could to help her fellow Filipinos in the city. Every Sunday, for over 30 years, she played host to dozens of MDWs who didn’t have anywhere to go, offering them a place to rest and a home-cooked meal. Having befriended the Philippine Consular staff, for whom she acted as an unofficial seamstress for their dresses, children’s clothing, and uniforms, she even helped a few distressed and abused MDWs bring their cases to the attention of the Consulate Office.

Helping others was in Qualee’s nature, with family always firmly at her core; she later helped her sisters Terry and Salva find jobs in Hong Kong and would regularly send money home to cover school fees for nieces and nephews.

In 1989, she gave birth to her youngest child, Alyssa, whom she left in the care of her Nanay in Jiabong. Then in 1994, with Qualee and Romy both working full-time jobs in Hong Kong and childcare becoming increasingly difficult, Aileen was sent to live with Nanay as well.

With an 8-year age gap and little in common aside from their last names, the sisters found it hard to connect. Aileen could barely speak Filipino, while Alyssa was fluent in Waray (the local dialect). Over time, they grew apart.

It wasn’t until years later that they formed a relationship, by which time Aileen had already started living on her own close to her school. Qualee could sense this rip in her family, and upon Aileen’s completion of her bachelor’s degree in Medical Technology, Qualee raised to her the prospect of returning to the Philippines for good.

“Your Dad and I are so proud of what you’ve accomplished. You finished your degree at such a young age and have such a bright future ahead of you,” she told Aileen. “I haven’t spent a lot of time with your sister, Alyssa, and I feel like if I don’t come back soon, I might not have a relationship with her at all. At the same time, you want to become a doctor, which would mean I need to stay in Hong Kong for four more years to pay for your tuition. I cannot decide. So, I want you to decide.” Aileen looked at Qualee and knew what the answer should be.

Migrant mothers who leave their families know of this pain all too well. When misfortune befalls their children, they feel guilty. When husbands cheat on them, they feel anger. Whenever the family needs money, they scramble to send it. If needs are not immediately met, they are sometimes branded as kuripot (stingy). Loneliness and anxiety are bottled up and tucked away, as they continue to work for their employers, most with little time to rest, and even less time to take care of their themselves and their mental health.

Filipino women are resilient, our spirits buoyed by our mantra ‘Kayod lang’, which translates directly as ‘just work hard’. But it has a deeper meaning; working through all the pain and tribulations, despite one’s own well-being, is the real essence of this phrase.

Despite everything that life threw at Qualee, she triumphed. Between her and Romy, they accomplished their goal – they built a better life for themselves and their children. Whatever hardships or successes they faced on their journey through life, they would often revisit the memory of the papaya; it was a moment in time that always kept them grounded. And they never ate papaya for dinner again.

Sadly, Qualee lost her Romeo a few years ago; after a long bout of illness, Romy passed away in May 2018. Nowadays, she spends her time minding her beautiful garden, tending to her pigs, helping the elderly as elected president of her local Senior Citizen Federation chapter, and doting on her beautiful granddaughter, Lily (Aileen’s daughter).

On our recent phone call, Qualee, my Mom, told me, “My only dream was for you and your sister to finish school. I am very lucky to have my children. I love you very much.” And this sentiment is echoed across the domestic worker community; the selflessness of their sacrifice for their families, Kayod lang. I, and countless other children of migrant workers, will forever be grateful. Maraming Salamat, Ma.

9dde49c3be6bac6166d59fb7abf39532)

(1)4b7355993ca6165c683913d00254e725)

6c2435b2dd0927f22b3222b88d21fb70)